In the Bundelkhand region of modern-day Uttar Pradesh, about 150kms east of Jhansi, is the tiny village of Jaitpur. At Jaitpur, during the winter of 1728-29, the 79-year old sovereign, Maharaja Chhatrasal Bundela was cornered by Muhammad Shah Bangash; Chhatrasal having lost all his forts one by one during the last two years. Jaitpur was the last bastion for the iconic Bundela warrior. The nearby Bundela kings of Datia and Chanderi had refused to help. In desperation the seasoned warrior sent a letter to Peshwa Bajirao I, with these lines, now a part of popular folklore:

जो गति ग्राह गजेन्द्र की सो गति भई है आज ।

बाजी जात बुन्देल की बाजी राखो लाज ।।

I am in the same plight in which the elephant king was, when caught by the crocodile. This Bundela is on the brink of losing, O Bajirao, come and save my honour

The letter triggered a series of events that led to significant geopolitical consequences in Central India and beyond. At a personal level for Bajirao, it resulted in his union with Mastani. A union, which had its own implications in Maratha history.

The story though, is bigger than that. It involved an ageing icon’s fight to protect his legacy, a gritty contest between two seasoned warriors, countless sacrifices in battlefield, and strategic masterstrokes by a legend on the rise.

The Key Players

![Raja Chhatrasal: See page for author [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://thecustodiansin.files.wordpress.com/2016/01/chhatrasal.jpg?w=760)

![Muhammad Khan Bangash: By Anonymous (http://expositions.bnf.fr/inde/grand/exp_039.htm) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://thecustodiansin.files.wordpress.com/2016/01/nawab_muhammad_khan_bangash_ca_1730_bibliotheque_nationale_de_france_paris.jpg?w=247&h=300)

![Peshwa Bajirao I: By Amit20081980 (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://thecustodiansin.files.wordpress.com/2016/01/bajirao_peshwa_i.jpg?w=300&h=225)

Clouds of Conflict

During the reign of Farrukhsiyar Bangash was granted the Jagirs of Sehand and Maudah in Bundelkhand. Diler Khan, a close aid of Bangash, was appointed to the charge of these Jagirs. Later, during the first year of Mohammad Shah (1719-20), the territories of Kalpi and Irichh were also assigned to Bangash. During the same year reports came that the Bundelas plundered Kalpi and some towns and killed one of the administrators. Diler Khan was sent with a sizeable force to punish the enemy, and he managed to drive the enemy away from the plundered towns. The matter was pressed further by Diler Khan, against the advice of Bangash, which led to a war against Chhatrasal. In the ensuing battle Diler Khan and five hundred soldiers were killed while charging against a much larger army.

Around the same time Bangash was appointed the governor of Allahabad province. His territory included the eastern part of Bundelkhand, which was annexed by Chhatrasal during his expansion and where he exercised effective sovereignty. Bangash received an imperial order to act against Chhatrasal in 1723. He started with a force of 15,000 but halted the campaign after making initial gains. Later, in 1727, another imperial order was obtained to march against Chhatrasal and his sons who had overrun more territories in Bundelkhand.

The Long War

Chhatrasal’s letters from late 1726 show a mad scramble to arrange defenses against Bangash’s invasion. Finally, on 3rd January 1727, Chhatrasal wrote a letter to his son Jagatraj:

You have written that Bangash has arrived. He is encamping at Nadpurwa and has sent a message to you asking when you desire to give battle for he wants to fight with you with pre-intimation and not to catch you unawares. He has also asked to fix the place. He has an army of 73,000 and 89 guns. And you have asked me to come at the earliest.

The auspicious day for our march from here is Mah Badi 9, so I will start accordingly from here. I have dispatched 35 rockets and 29 guns which would reach (in due time). Mah Badi 7, Samwat 1783, place Mau.

Bangash was at the door and was asking for a pitched battle.

The war was on!

The first battle became an insignificant footnote in what was going to become a gruelling campaign for both sides. Early momentum was with Bangash. He knew the territory well from his days as a mercenary. In the initial thrust he captured the forts of Luk, Chaukhandi, Garh Kakarelie, Kalyanpur, and Ramnagar. A long siege began at Tarahwan by Bangash’s son Qaim Khan against Chhatrasal’s grandson, defending from inside. While this siege was on, Bangash continued to overrun other forts. A fierce battle in Ichauli (12th May 1728) resulted in nearly 5,000 casualties for Bangash and 13,000 for the Bundelas. After each battle, the harrowed Bundelas moved to the next fort or took shelter in the jungles and ravines. Bangash’s army pursued them vigorously.

This pattern of battles continued until Chhatrasal was cornered in Ajhnar in July 1728. Fortunately for Chhatrasal, monsoon arrived, which made placing of explosive mines quite difficult for the enemy to force a breach, for the next 4 months. Bangash was also starting to feel the shortage of funds and was getting disappointed from the lack of interest from the Imperial court. The action continued regardless. On 1st November 1728 Ajhnar fell. Chhatrasal shifted to Jaitpur, his last bastion. Tarahwan, in the east, also fell on 12th December 1728. This siege had resulted in more than 2,000 casualties for the Bundelas who offered tough resistance. The whole focus now shifted to Jaitpur, the last arena of this long drawn war.

Two years had passed under great difficulties and losses for both parties. During the course of this war, the nearly 80-year old Chhatrasal and his sons had received injuries. On one occasion his wife had led the action. The loss of life ran in several thousands for both sides.

Finally, Chhatrasal decided to surrender. Negotiations were opened and Bangash sent a message to the Mughal Emperor asking for terms of the settlement. He was hoping to bring his prisoners personally to the Imperial court. Chhatrasal and his family waited for their fate camping in the hills outside the fort. Sometime in December 1728 news arrived, that Giridhar Bahadur, the Mughal governor of the neighbouring province of Malwa had been killed by the Marathas in a battle led by Chimaji Appa, Bajirao Peshwa’s brother. Bangash probably kept an eye on the situation but didn’t see an immediate threat. He was so certain of his victory, he allowed a large part of his army to go back on leave.

Holi was approaching on 15th March, 1729. Chhatrasal’s sons requested that the family be allowed to move to Suraj Mau. Bangash consented, confident about his position and partly on account of Chhatrasal’s old age. On 12th March, 3 days before Holi, Bangash got the shocker.

Bajirao was just 11 kos (approx 22 miles) away, ready, with a large army.

Peshwa’s Arrival

Back in August 1728, Dado Bhimsen, one of the Maratha envoys in the Mughal court, wrote a letter to Bajirao. The letter was largely about Mughal preparations against the threat of Maratha invasion in Malwa. But it also contained the following lines:

“येक पत्र छत्रसाल बुंदेला त्यांसी बंगसासी लड़ाई आहे दसरा जालियावरी आमच्या फौजा त्या प्रांतास येतील, तुमची कुमुक होईल म्हणून लिहिले पाहिजे”

You (Bajirao) should write a letter saying that “Chhatrasal Bundela and Bangash are engaged in a battle. Our armies will come to that region after Dussehra and help you.

Bhimsen’s letter also mentioned Sawai Jai Singh’s support to the idea of Bajirao’s intervention.

At this time, Bajirao was busy collecting Chauth, exercising the recently acquired right from the battle of Palkhed. Peshwa’s ledger entries show an interesting pattern in his movements in subsequent months. He started from Pune in October 1728 and accompanied Shahu on pilgrimage to Tuljapur on 9th November 1728. From then on he moved north-east, all the while addressing administrative issues and collecting chauth. He maintained constant correspondence with Chimaji in Malwa. The Marathas had recently conquered Malwa and were besieging Ujjain where the slain Mughal governor’s nephew had put up a resistance.

The correspondence between Bajirao and Chimaji shows how Bajirao thought and worked. Bajirao and Chimaji shared a close bond with each other, were in constant touch, and carefully coordinated their moves.

On 29th December, 1729 Bajirao wrote to Chimaji that he intends to go “wherever hunger can be satiated (“Poat Bharavayas Jikade Jaane Tikde Jaaun”). It referred to collecting money. Shahu had incurred a large debt in raising the army and fundraising was a huge priority for the Peshwa. Subsequent letters show Devgarh to be the next destination of his march. Devgarh was ruled by a Gond tribal king, and covered the territory between Nagpur and Jabalpur. Finally, on 4th January 1729 Bajirao wrote about his intentions to proceed towards Bundelkhand after settling Deogarh. In another letter he asked Chimaji to be ready to proceed towards Bundelkhand, if needed. A small battle took place at Deogarh, and the matter was settled with ease. Sometime in February 1729, in Garha, he received the famous letter from Chhatrasal seeking help.

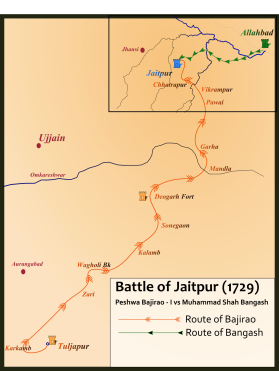

Bajirao now moved with his trademark speed, crossing great distances in a day. Accompanied with a 25,000 strong cavalry force under 12 commanders, he went via Khajuri, Pawai towards Bikrampur. Peshwa’s ledger for 9th March at Bikrampur mentions sending two messengers towards Chhatrasal and one scout to conduct reconnaissance on Bangash. The intent was clear from then on. Next day, Bhartichand, a son of Chhatrasal, met him in Rajgarh. He reached Mahoba on 12th March, where Chhatrasal’s sons welcomed him. On 13th March he met Chhatrasal who presented of 80 mohars to him. The combined force, now swelled to 70,000, was now moving towards Bangash’s encampment in Jaitpur. Many local rajas and zamindars who were on the fence throughout the war, recognised the momentum and added to the numbers.

Endgame

The rescue force reached within 1 Kos from Bangash’s camp and set about its business right away. This was a battle hardened army, very well experienced in lean warfare tactics. The first day, they raided the cattle of the camp followers. Small skirmishes occurred resulting in the loss of 3 soldiers from the besieging army. The next day, Bangash’s camp was surrounded from all sides. Camels and bullocks who had ventured out grazing from the camp were driven away. This was followed by a few skirmishes and casualties. The enclosure tightened further. All roads were closed and supplies were completely cut from all side. Prices of foodgrain rose rapidly with the worst quality of grain selling at rupees 20 per ser. Bangash’s army tried to force their way out with surprise raids. The Marathas made their incursions in the Bangash camp and retreated in the hills of Ajhner where they were largely camped. But this was a lost cause for Bangash. Qaim Khan, Bangash’s younger son, who had been engaged elsewhere, rushed to his father’s rescue with supplies and reinforcements. Bajirao sent a strong detachment under Pilaji Jadhav to intercept Qaim Khan, which created a gap in the perimeter. Thousands of Bangash’s soldiers used this opportunity to escape, leaving their commander to fend for himself. Pilaji Jadhav engaged Qaim Khan at Supa, which resulted in an utter rout of Qaim Khan’s army and a large booty for the Marathas.

Bangash had meanwhile barricaded himself inside Jaitpur fort. The besieged suffered severe shortage of food. Gun-bullocks and horses were slaughtered for food. Bajirao’s orders to his guards were to allow a safe passage to anyone surrendering his arms. A great many did, leaving Bangash with a skeleton of a force.

Bangash sent urgent messages to Delhi seeking help. After repeated SoS, the Emperor ordered his Bakshi, Khan Dauran to proceed towards Jaitpur. Khan Dauran dragged his feet and halted after a short march.

The siege went on for 4 months. Monsoon was about to set in, when cholera broke out in the Maratha army, resulting in over thousand deaths. Bajirao decided to return back. The job was done. Chhatrasal continued with the siege. Negotiations were again opened between Bangash and Chhatrasal. Finally, Bangash signed a covenant to never invade Chhatrasal’s territories again. In August 1729 he was allowed to leave, letting him out of his misery. Qaim Khan met him en-route to Mahoba, urging to resume the fight again, but Bangash was not interested in it anymore. He crossed Yamuna at Kalpi on 23rd September, and never looked at Bundelkhand again.

Aftermath

The battle ended Bangash’s connection with Bundelkhand. He retained the nominal authority of those Jagirs in Mughal books but never obtained any revenue from it. He continued to plead with the emperor and wazir to recover his battle expenses without success. During Nadir Shah’s invasion of India, Bajirao had sent a letter urging all Indian nobles to unite. Bangash was one of those who agreed with the cause, but in his letter to Bajirao he referred to the futility of his life in a couplet “dunya nakshe ast bat-ab o ziyada az sirab nast” (The world is nothing but an imprint on water, there isn’t much thirst left now). Once in a while he wrote to Harde Sah to recover a cannon and dues promised by Harde Sah in some previous agreements. He referred to Harde Sah as his friend and instructed him to take care of his properties. The legitimacy of Bangash’s claims remained jumbled in the 18th century world of fluid sovereignty. His ability to enforce his right only as strong as his sword, which he had lost decisively at Jaitpur. Though it can be argued that the intrigues and politics of the Mughal court failed him more than his sword. Irrespective of these setbacks, the warrior Pathan had clearly traversed a great journey since his days as a small time mercenary. He remained a somewhat significant figure in the Mughal court until his death in December, 1743. His death was likely caused by an abscess in his neck. Lying on his deathbed, he shot an arrow at the roof to prove his God given strength. He died 3 hours later. He is interned in the village of Nekpur Khurd in Farrukhabad.

A grateful Chhatrasal offered approximately one third of his kingdom to Bajirao, adopting him as his son. Chhatrasal died in December 1731, less than two years after the battle. The poet-warrior had lived a lived a long, vigorous life and his career trajectory had emulated that of his role model Shivaji in many ways. In hindsight, Shivaji’s advice had worked out quite well for him. His giant footprints can be seen in the landscape of Bundelkhand and in the oral traditions of Bundeli people. A memorial for him was built in Dhuvela, the expenses for which were shared by his sons – Hirde Sah, Jagat Raj and Bajirao.

Between 1728 and 1729, all of central India had gone out of Mughal control, never to return. Marathas were now staring in all directions – especially Orissa, Bengal and … Delhi.

The Mughal Empire was crumbling and it’s foundation was being hammered hard by a young and impatient Peshwa who, clearly, had the “head to plan and the hand to execute“.

Notes

- The much cited phrase about Bajirao “head to plan and the hand to execute” was first used by J. Grant Duff in ‘A History of the Mahrattas’

References

- Sardesai, Govind Sakharam. (1931-34). Selections from the Peshwa Daftar, Vol 13 & 22

- Gupta, Bhagwan Das. (1980). Life and Times of Maharaja Chhatrasal Bundela

- Gupta, Bhagwan Das. (1999). Contemporary Sources of the Medieval and Modern History of Bundelkhand, Vol 1

- Irvine, William. (1878). The Bangash Nawabs of Farrukhabad. Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Part 1- IV, 259-383

- Dighe, Vishvanath G. (1944). Peshwa Bajirao I and Maratha Expansion

- Sarkar, Jadunth (1932). Fall of the Mughal Empire, Vol 1

A remarkable effort I must say.

When It goes

On 12th March, 3 days before Holi, Bangash got the shocker.

Bajirao was just 11 kos (approx 22 miles) away, ready, with a large army.

The writing gives a shocking interval quotient(as in Hindi Movies…with the suspense and thrill yet to arrive).

A mercenary executing the orders of a half-emperor against a stalwart. A great warrior inching forward to create a history.A not so less Chimaji appa in the backyard. The history was going to be rewritten and to be remembered for centuries.The rains, the speed of Bajirao , the habitual leaving in lurch tactic of Half emperor and the aging Great Bundela waitin for help……

A theatrical display of events at a time when not many examples of examples of strategic help were there ..this piece shows how history can be written in favour.

Chhatrasal regaining his territory.. Bajirao getting foothold in Bundelkhand and Mastani..Bangash alive ….a not so sad ending

Very well sequenced. Equal respect to all characters.History is made by ones but preserved through writings .Overall I can see a good script writer

LikeLiked by 2 people

I think I should have used some of your sentences in the summary . You have done it better than I did.

LikeLike

A thorough, insightful and well-informative article indeed. I felt as if I am reading some chapter from Jadunath Sirkar’s book. In spite of being a big article, I didn’t feel lost or disinterested anywhere.

Please keep up the high-standards created herewith.

Suggestion – please consider using Inkscape to make your custom maps than google-maps.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you very much for the kind words! Comparison with Sarkar’s work is a very big compliment.

We had to cut some sections out to keep the story to this length. The handover of the territory between Chhatrasal’s son and Bajirao, Sawai Jai Singh’s involvement, and whatever we can tell accurately about Mastani’s origin .. some of the offshoots of this story, we’ll take up some later date.

LikeLike

Hello Sandeep. Thanks for the comment and the suggestion on Inkscape. As of now, none of us have expertise in graphics. We are seeking volunteers to help us create illustrations, artworks, and related content. If you know someone, who can help (as a labour of love) do connect us. Due and prominent credit will be given. 🙂

Once again, thank you for the encouragement.

LikeLike

Hello Atul.. sadly I do not know anybody in this. I am planning to learn Inkscape since a year now – since I love history, maps and graphics … it’s ‘the’ thing for me. But yet couldn’t find time for it.

When/if I learn it, I will be happy to help you guys.

LikeLiked by 1 person

We look forward to that! 🙂 In the meanwhile, I look for your support and contribution in any way you can.

LikeLike

Beautifully written. Very dramatic narration. The articles flows like a story and reveals few points which I didn’t know earlier. As Samir mentioned, some parts do feel like clipped. Would really like to read a longer version or even a book on this.

LikeLiked by 1 person