The dense overgrowth of vegetation inside a ten feet boundary wall makes it almost impossible to see what is inside. The property is under legal dispute and the boundary wall is the result of it. One has to climb up, down, and around to get a glimpse of what looks like an outer wall of the structure. Situated near the Brahmavart Ghat on the banks of Ganga, about 25 km north of Kanpur, this was the last abode of the last Peshwa.

At the ghat, amidst red stone structures, priests tell tales spanning eternity and recite mantras handed down over countless generations, understandably oblivious to that part of 1800s when a community thrived and got uprooted, when famed warriors took their early steps on the streets here, and when blood spilled and mixed with the waters of the Ganga.

The community was established here in consequence of events that occurred 1300 km away in Pune. The Peshwa Baji Rao II (10 January 1775 – 28 January 1851) presided over an empire in decline. Many consider the Treaty of Bassain (Vasai) of 1802 to be a significant step towards the decline, in which the East India Company (EIC) curtailed the power and influence of the Peshwa to a large extent. The Peshwa Baji Rao II continued as a ‘nominal head’ under the control and influence of the EIC, when he was returned to seat of the Peshwa, sans the title, in May 1803.

The Third Anglo-Maratha War (1817–1818), for all practical purposes, marked the end of

the Maratha Empire in India. The seeds of this war were sown on the arrival in Pune of Gangadhar Shastri, a “company-endorsed” envoy of the Gaikwad of Baroda, to negotiate a long disputed revenue settlement. Gangadhar Shastri was murdered in Pandharpur in July 1814, and the EIC took this as a ruse to further curtail the power of Baji Rao II, extracting large amounts of land and imposing several other restrictions, ensuing the battles of the Third Anglo-Maratha War, which marked the final downfall of the Peshwa, who surrendered to John Malcolm, then serving as the company’s officer in charge of Central India, at Mhow in May 1818. The terms of his surrender required him to give up all his titles and claims of sovereignty, and to leave for “Hindustan” without a day’s delay. While the discussions were on Malcolm arranged for the news to be leaked to other Maratha officers in order to hasten the process. The terms of surrender included an agreement for annual pension of at least 8 lakh rupees for the maintenance of the ex-Peshwa and his followers.

After some deliberations Baji Rao II agreed, arriving at Malcolm’s camp at Khairi on 2nd June, 1818. Khairi lies in the Nimar region, where at Raverkhedi his illustrious grandfather and namesake – Baji Rao I – had breathed his last, right after ending the centuries of Mughal monopoly on collecting tolls on Narmada crossings. Circumstances had changed immensely in a century.

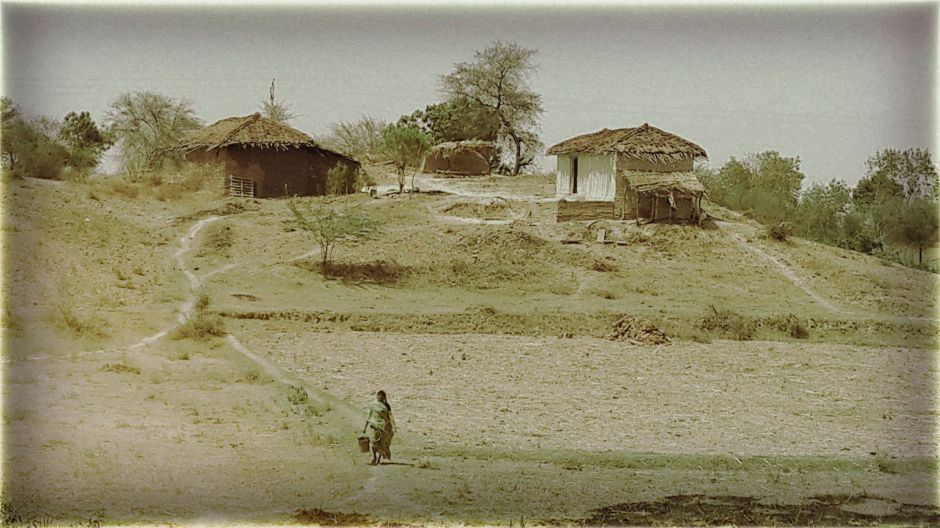

A military escort was arranged to take the ex-Peshwa to a yet undecided destination up north. Lt. John Low, Malcolm’s assistant, was assigned to lead the escort at Baji Rao’s request. The party proceeded towards north via Rajputana, skipping the Bundelkhand route due to political unrest and monsoon. The word went out and people from far off districts came to see the Peshwa in person. The final destination of Peshwa’s exile was still not decided. Varanasi, initially a choice of Peshwa’s advisors, was rejected by the Governor General. Mathura was also rejected as it was on the frontier of the company’s territories. Baji Rao’s advisors were not too keen on some other cities that were considered. Gorakhpur had no famous temple of distinction, Gaya was considered to be too expensive, Munger was too deep in the company’s territory.. Finally Bithoor was finalised as the destination. It was conveniently located near Kanpur where the British had a large cantonment and had an existing community of some Marathi speaking people. Thus, the ex-Peshwa, who had spent his childhood in captivity in Dhar, settled again into a life of confinement in Bithoor.

John Low, who had developed a good relationship with Baji Rao, was appointed the first commissioner to manage the affairs in Bithoor. Living on an annual pension of Eight Lakh rupees, with a large entourage to support, Baji Rao built a palace in Bithoor covering 35 acres. A modest community gathered around him, from which he appointed officers with titles similar to his former administration. Part of the pension was spent in  building public infrastructure. Stones from Mirzapur and wood from Patna were purchased for the construction of a temple, a ghat, a house for priests at Benares. Additional stones were procured from Mirzapur for a temple at Bithur. As of December 1837, the number of people living on the estate amounted to 7132, which included “500 sowers and 450 sepahis”. Ramchandra Pant, formerly a Subedar in Peshwa’s service in Carnatic, acted as his Dewan and held that position until Baji Rao’s death. Subedar Pant had commanded an army of 5000 in his earlier days and had fought against the British; had seen wounds in action, but in the changed circumstances, he was considered to be a trusted ally by British commissioners. Loans amounting to several lakhs were extended by the ex-Peshwa to the British, secured partly with some help from Ramchandra Pant.

building public infrastructure. Stones from Mirzapur and wood from Patna were purchased for the construction of a temple, a ghat, a house for priests at Benares. Additional stones were procured from Mirzapur for a temple at Bithur. As of December 1837, the number of people living on the estate amounted to 7132, which included “500 sowers and 450 sepahis”. Ramchandra Pant, formerly a Subedar in Peshwa’s service in Carnatic, acted as his Dewan and held that position until Baji Rao’s death. Subedar Pant had commanded an army of 5000 in his earlier days and had fought against the British; had seen wounds in action, but in the changed circumstances, he was considered to be a trusted ally by British commissioners. Loans amounting to several lakhs were extended by the ex-Peshwa to the British, secured partly with some help from Ramchandra Pant.

Baji Rao’s younger brother Chimaji Appa II had settled in Varanasi where one Moropant Tambe from a village named Venu near Matheran worked with him. After the death of Chimaji, Moropant Tambe moved to Bithoor with his daughter – Manikarnika. Somewhere in the corridors of the estate little Manikarnika, also known as Chhabili, learned writing, horse riding and weapons handling. When Manikarnika was in her early teens, some intermediaries arranged for her marriage with the Raja of Jhansi, making her the Rani of Jhansi.

One Pandurang Yewalekar managed Baji Rao’s religious and household affairs. Pandurang had been in employment with Peshwa from Pune and followed him to Bithoor with his family. One little child in this family was Ramchandra Pandurang, who was later known as Tatya Tope.

Baji Rao did not have any male heir, a fact which proved to be very consequential under the doctrine of lapse. He got married six times, but none of the marriages produced a male heir. In later years, he adopted three sons and a daughter, the eldest of them Dhondopant, became his heir apparent.

With time the Peshwa settled into life in exile. He grew close to the British commissioners, so much that John Low wrote to his mother that the ex-Peshwa had tears in his eyes when he left Bithoor for his next posting. There were 4 commissioners during his exile in Bithoor. As the time lapsed, the British stopped worrying about any reprisal of Maratha power. The commissioners borrowed Peshwa’s guard for security and ceremonies.The military apparatus in Bithoor was a heavily curtailed setup, mostly required to safeguard the pension amount which was delivered monthly. Baji Rao had grown up under the highly religious environment under his mother. He spent a lot of time in religious ceremonies. Religious festivals were celebrated with full rigour. The Bithoor palace was decorated lavishly, with expensive carpets, paintings and European style furniture. Parties were organised, attended by many British people from Bithoor and Kanpur. Life in Deccan was missed at times. Occasionally, envoys were sent to Deccan to arrange for flower plants and to get a particular kind of oil to treat Rheumatism.

Baji Rao lived in Bithoor for 32 years, much longer than the company had expected him to live. As time went by, he attempted to fill the loss of real power with esteem in titles and pageantry. Any chances of regaining his earlier power melted away in time as people close to him died and the power of the British empire became all pervasive. Back home, his former adversaries – Montstuart Elphinston, James Grant Duff and John Malcom – had published memoirs and histories of the Maratha empire, writing extensive accounts of the military conquests of his predecessors and his ancestors.

On 26th January 1851 Baji Rao fell ill and was attended by British doctors, who confirmed the impending news to the commissioner. He died 2 days later, at the age of seventy-seven. Baji Rao was born in difficult circumstances and carried a complicated legacy of his father Raghunath Rao. The title of Peshwa thrust him in the middle of a major geopolitical crisis without much training or resources to deal with it. He would not have known, as he breathed his last, that his death would thrust Dhondopant, now known as Nana Saheb, into another geopolitical crisis.

Part 2Part 2 : Baji Rao II and the Establishment of Bithoor

Sources:

- Gupta, P.C., The Last Peshwa and the English Commissioners, 1818-1851

- Misra, Anand Swaroop, Nana Saheb Peshwa and The Fight for Freedom, 1961

- Kincaid, D., British Social Life in India 1608 – 1937

- Dodd, George, The History of the Indian Revolt and of the Expeditions to Persia, China, and Japan: 1856-7-8, With Maps, Plans, and Wood Engravings

- Trevelyan, George Otto, Cawnpore, 1910

- Naravane, Dr. M. S., Decline and Fall of the Maratha Empire, 2008

- Richard Wellesley Marquess Wellesley, Notes Relative to the Late Transactions in the Marhatta Empire, Fort William, December 15, 1803

- Government Central Press, English Records of Maratha History. Poona Residency Correspondence, Volume 13, 1968

- Indumati Sheore, Tatya Tope, 1980

Edit: An earlier version of the article mentioned the location of Gangadhar Shastri’s murder as Pune, it has been corrected to Pandharpur.

![By James Prinsep (British Library [1]) [Public domain], <a href=](https://thecustodiansin.files.wordpress.com/2016/05/the_man_mundil_or_hindoo_observatory_benares_by_james_prinsep_1832.jpg?w=760)

![By w:user:Planemad [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://thecustodiansin.files.wordpress.com/2016/02/tc-featured-images-007.jpeg?w=940)