A few decades should count as a small blip in the long history of human civilization. The last few decades, however, have been immensely transformative for the human race. Many objects and experiences that were a persistent part of human story in the preceding millenniums are fading away quite fast. Mass hunger was one of them. It came often, it came hard and it left some deep hollow spaces in the tree of humanity.

The story of an officer’s efforts in dealing with mass hunger in a small town in Central India in 1833, and eyewitness accounts of other famines offer us an insight into what it was like to live through a calamity like this.

Background

The end of Anglo-Maratha wars in 1818 effectively concluded the British conquest of India, with the British now gaining control of most of India. Among the newly conquered territories a large portion was what is now known as the state of Madhya Pradesh. The ancient land of Gonds, Satavahanas, Guptas, Chandelas, Bundelas, Mughals and Marathas was now ruled by the mega corporation: the East India Company.

The company which was initially chartered to explore the “trade of merchandize” with India was now deeply ensconced not only in the matters of Diwani (Revenue and Civil Administration), but also for Nizamat (Criminal and Police Administration). People in central India who recognised their rulers through clans, now saw officers coming from far away lands as representatives of the faceless corporation. Some of these officers found themselves in a position where their actions had a very significant impact on a large number of people. Many officers were acutely aware of the burden tied to their bureaucratic strings. Among them, there was Sir William Henry Sleeman.

Sleeman soon found himself tackling the wide array of administrative tasks in the course of his postings in the region. Among them were matters of revenue collection, law and order, Sati burnings and other social reforms, treasury and mint, agriculture, thuggie and famines.

The Hunger Spiral

Famine was a frequent occurrence. Droughts, floods, warfare, locusts, monsoon, and many other factors caused frequent famines in medieval India. The Jataka tales, Jain literature, and other ancient texts mention severe famines in India. Contemporary writings during Mughal period mention severe famines of great intensity. During the reign of Shah Jahan some three million people are said to have perished due to famines.

It often started with crop failures, which led to food shortage, and increase in the price of food grain. In those closed loop economies, without much transportation and communication links with the outside world, speculation played a vital role. Nearly every generation had seen serious famines and people relied on old tales to make significant decisions that weighed heavily on their families’ fate. One old saying went:

सावन कृष्ण एकादशी, यदि गरजै अधिराक। तुम पिय जाओ मालवा, हम जावें गुजरात।।

(If there are heavy thunders during the Krishna Ekadashi of Sravan month; oh father, you go to Malwa and I will go to Gujarat)

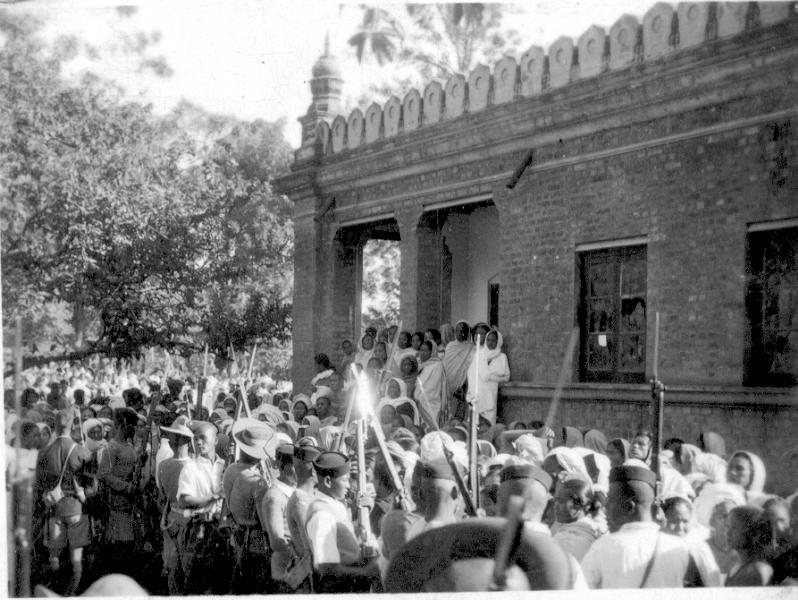

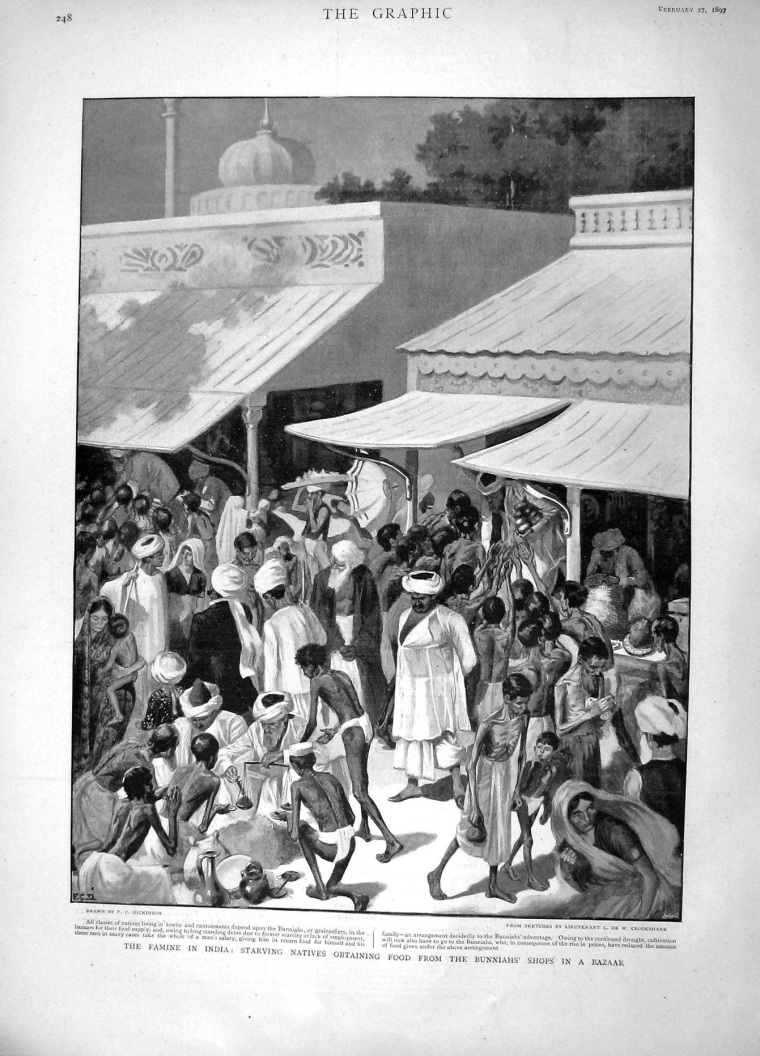

Malwa was seen as a more fertile land where famines were less frequent. With the spread of panic, started a trail of migrations. Not knowing what to do, poor families abandoned their farms, homes, and cattle and often moved towards the centres of authority – local rulers or the administrative headquarters. Many rulers organised charity kitchens. As the famines intensified, torrents of poor, famished people flowed to cities.

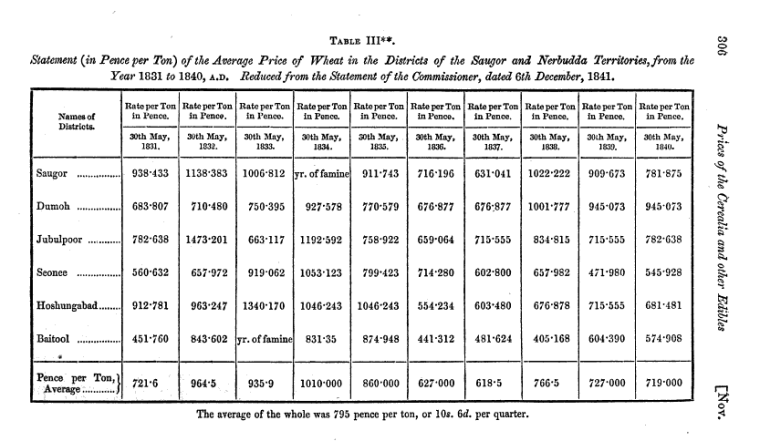

At the sight of scarcity, the agriculture economy froze like a scared animal. The value chain consisted of farmers, traders, transporters, financiers, and consumers. Traders would often hoard the grain, sensing headwinds. Shortage of cattle added to the transportation challenges. The produce was carried on bullocks, covering 6-8 miles a day. Prices doubled for every 100 miles of transportation, and tripled in a season of scarcity. Insolvency of any debtors crippled the money supply in the markets dominated by small, closed communities. With the complete shutdown of a functioning society, the focus eventually came to the one and only essential commodity – FOOD

Those Sights, Sounds and Stench

Contemporary observers of famines describe a society stricken with hunger in chilling detail.

Still fresh in memory’s eye the scene I view,

The shrivelled limbs, sunk eyes, and lifeless hue ;

Still hear the mother’s shrieks and infant’s moans,

Cries of despair and agonizing groans.

In wild confusion dead and dying lie;–

Hark to the jackal’s yell and vulture’s cry,

The dogs’ fell howl, as midst the glare of day,

They riot unmolested on their prey !

Dire scenes of horror, which no pen can trace,

Nor rolling years from memory’s page efface.~ Charles John Shore Baron Teignmouth (referring to the Bengal famine of 1770)

(Memoir of the Life and Correspondence of John, Lord Teignmouth, Volume 1)

Poor people, now homeless, without any possessions, were seen wearily dragging themselves along major roads. Those left behind in their villages, each passing day played Russian roulette with death; weighing the odds of improvement in the situation against the risk of abandoning their home, while they had the means and physical energy to do so. The definition of “food” started changing. Seed-grain was consumed, damaging the prospects of next year’s crops. Shrubs like Jharberi and many plant seeds became a large portion of diet. Grass, tree leaves were consumed. When the famines intensified, many cattle were slaughtered or abandoned by their owners.

The abandoned animals howling in agony of thirst and hunger went eventually silent. The stench of animal carcasses was felt in the air. The surviving animals, in their bare bones, scourged for food in shrubs, roots, and trees in extreme desperation. F.H.S. Merewether describes:

As we were coming back from the court-house, the Commissioner pointed out to me a few frameworks of cattle on the wayside; they were absolutely burrowing in the ground, like pigs, to get at the roots.

And it subsequently moved to humans. Younger children, in absence of prolonged absence of meals, were the most vulnerable and often perished quickly. In desperation, many children were sold into slavery. The practice of selling children during famines was an old one. Ain-e-Akbari mentions that Akbar had legalised the practice during the times of famines and distress, and gave their parents an option of buying them back later.

The malnourished children developed a swollen abdomen due to protein deficiency, a symptom known as Kwashiorkor. This was a fatal stage and very few children survived after that. The children tottered with a feebly, bereft of any childlike demeanour. Merewether describes:

One of the first objects I noticed on entering was a child of five, standing by itself near the middle of the enclosure. It’s arms were not so large round as my thumb its legs were scarcely larger; the pelvic bones were plainly shown; the ribs, back and front, started through the skin, like a wire cage. The eyes were fixed and unobservant; the expression of the little skull-face solemn, dreary and old. Will, impulse, and almost sensation, were destroyed in this tiny skeleton, which might have been a plump and happy baby. It seemed not to hear when addressed. I lifted it between my thumbs and fore-fingers; it did not weigh more than seven or eight pounds. Probably its earliest recollections were of hunger, and it could never have had a full meal. It was now deserted by those who had brought it into the world, or they were dead; its own life would be gone in a day or two. Its skin was quite cold. dry and rough. Pain had been its only experience from the first; it had never known or imagined the comforts that babies have.

As for adults, death came in many forms. Tribals wandered into forests in search of food, disoriented, and died of exhaustion there. Shortage of herbivorous animals caused wild beasts to wander into human territories and many people were killed by tigers. Many families chose to kill themselves with opium or other means after having all provisions exhausted. Pandita Ramabai, a famine survivor describes:

At last the day came when we had finished eating the last grain of rice – and nothing but death by starvation remained for our portion. Oh, the sorrow, the helplessness, and the disgrace of the situation •••• We assembled together and after a long discussion came to the conclusion that it was better to go into the forest and die there than bear the disgrace of poverty among our own people. Eleven days and nights – in which we subsisted on water and leaves and a handful of wild dates – were spent in great bodily and mental pain. At last our dear old .father could hold out no longer the tortures of hunger were too much for his poor, old, weak body. He determined to drown himself in a sacred tank nearby and thus to end all his earthly suffering ••• It was suggested that the rest of us should either drown ourselves or break the family and go our several ways.

Weakened bodies crawled around waiting to die, trying to avoid being mauled by impatient jackals and vultures. Sleeman wrote about the famine in Sagar:

At Sagar, mothers, unable to walk, were seen holding up their infants and imploring the passing stranger to take them in slavery, that they might at least live. Hundreds were seen creeping into gardens, courtyards, and old ruins, concealing themselves under shrubs, grass, mats, or straw, where they might die quietly, without having their bodies torn by birds and beasts before the breath had left them.

The Intervention Dilemma

In 1833 Sleeman was in the middle of his famous Thuggie trials, while serving as a magistrate in Saugor (Sagar) district in Bundelkhand. The autumn rains failed, and the spring crops could not be sown owing to the hardness of the ground, caused by the premature cessation of the rains, followed by the outbreak of famine. As the famine intensified in the countryside, streams of people started migrating towards Sagar, causing the all too familiar explosive situation.

Sagar was a major cantonment centre. Major Gregory, the military officer posted in Sagar, unsure of the future supply of grain and apprehensive of discontentment among his soldiers, decided to procure a large supply of grain at high prices. Everyone, consumers as well as traders, saw this as a certain signal of an impending crisis. Soon the markets got exhausted of any known supply of food, and the trade stopped.

Hoarding compounded the problem. The merchants hid the grain in underground granaries, pits inside their homes and warehouses. The greed for profit caused the merchants to accumulate grain, and the fear of rioting or coercive action by authorities caused them to hide it. This made it hard for authorities to estimate the actual quantity of grain available in the market. Quite often the grain rotted in the traders pit without reaching the markets. This led to authorities raiding the traders storage, confiscating it or forcing them to sell it at a discounted prices. Arthashastra by Kautilya recommended making the rich “vomit (वमनं)” their wealth during harsh famine.

With the intensifying famine, shortage of food and arrival of migrants, Sleeman faced the pressure to act against the traders. The kotwal of Police declared that a crisis was impending and the police and others would be unsafe unless such action is taken.

Sleeman had been a long advocate of free trade. His concern was that the forcing a trader to sell his stock deprived him of his cash flow. In absence of incentives and the fear of such actions discouraged the traders to import grains from elsewhere, which in the ensuing period made things much worse.

But was there any grain from other districts to import? Sleeman got an estimate of stock in Jabalpur and other places, which indicated that there was stock.

He showed his pledge to Major Gregory, assuring that no amount of clamour should ever make the administration violate the pledge given to the traders, and he was prepared to risk his situation and reputation as a public officer upon the result.

This proclamation was issued in the city in the afternoon and further police force was deployed to provide assurance to the traders.

As Sleeman had hoped, the markets started to open. Grain started to appear in the market, and traders, with their apprehensions reduced and cash flows operating again, sent out to import grain from other districts. The high prices attracted more people to venture into the trade, and soon the prices started coming down.

The crisis, at least for a while, was avoided.

Epilogue

A lot of water has passed under those medieval bridges crossed by Sleeman in the 1800s.

He went on to become the Commissioner for the Suppression of Thuggee and Dacoity, and later a resident a Gwalior and eventually at Awadh, with Wajid Ali Shah. After spending 47 years in India, he died in February 1856 near Ceylon (Sri Lanka) at the age of 67, on the way home. He was buried at sea.

Sleeman’s footprints can be traced across the landscape of central India. Among them, a bounty of literature describing the world he saw. Statistical records of his time, a variety of sugarcane he brought from Fiji, first Dinosaur fossils in India found by him, the modifications he made in the Indian penal code, the institutions he establishe and a little village called Sleemanabad near Jabalpur.

The British administration presided over many severe famines, causing several millions of deaths. India gained independence in 1947. The Food Corporations Act of 1964 resulted in the establishment of Food Corporation of India in 1965.

In 2012, Madhya Pradesh became the second largest wheat-producing state in India, much of the wheat comes from the region around Sagar. There has not been a single large-scale famine in India since independence. That stench, those shrieks and groans, howling of animals and that stench of death have been largely forgotten.

Sleeman’s collectorate in Sagar was demolished in 2016 to make way for new construction. Few other relics of that era survive.

Etched in the DNA of humanity, there are traces of events that created major voids in the genealogy trees. Somewhere around them there are also markers of a day in a bygone era when some hungry people were able to eat.

References

- Memoirs on the History, Folk-lore, and Distribution of the Races of the North Western Provinces of India Link

- Rambles and recollections of an Indian official

by Sleeman, Sir, William Henry Link - Indian Famines: Their Historical, Financial, & Other Aspects, Containing Remarks on Their Management, and Some Notes on Preventive and Mitigative Measures Link

- The Starvation Process: Dearth, Famishment and Morbility. Link