The Background

Babur descended from the Hindukush mountains into the plains of Punjab and created an empire spanning from Badakhshan to Bihar.

He had many sons out of whom only four were important – Humayun (the eldest), Kamran, Askari and Hindal (the youngest).

Babur died in 1530 leaving a fragile legacy in the more fragile hands of his 20-year old son Humayun, challenged by the nobles and Kamran. Every opponent was waiting for the right opportunity to hit. Humayun, however, relied on astrology and stars instead of SWOT analysis (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats).

Indian Enemies and Clashes

Humayun had to face two threats – Sher Shah Suri of Bihar and Bahadur Shah of Gujarat, who had also captured Malwa and Mewar. Humayun failed to capitalise on his initial upper hand over both the rivals. Although Bahadur Shah was killed by the Portuguese in 1537, Sher Shah Suri took Bengal in 1538 and emerged as the biggest single threat to him.

The Run and Chase Game in India

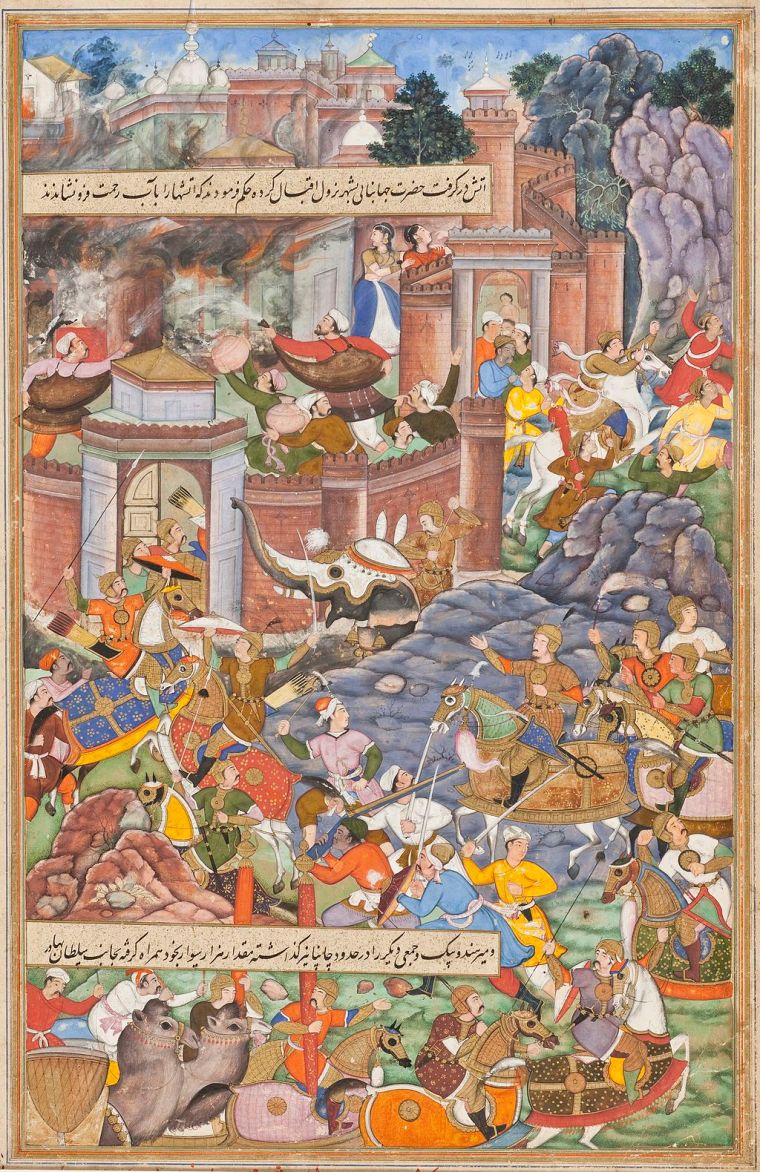

Humayun fled Delhi to Lahore along with his family, few loyal courtiers, and bodyguards. At this time, his brother Kamran was hostile as ever and Askari was with Kamran at Kabul. Hindal was 21, and had proved his administrative capabilities in the past decade. So his ambitions couldn’t be discounted either. Apparently Humayun was not welcome at Kabul. Instead, Kamran tried to join hands with Sher Shah.

Sher Shah was quick in capturing the Punjab. Sensing the danger of possible nexus between the pursuing Afghan and his brothers, Humayun was left with no choice except fleeing south across the Thar desert to Sindh, then ruled by the Arghun sultan Hussain Shah. Fortunately for Humayun, Hindal pledged allegiance to him.

Humayun reached Sindh in 1541 and unsuccessfully tried to win over Hussain Shah Arghun, an unexpected favour from a person whose father was expelled from Kandahar in 1522 by Humayun’s father, Babur. Although Hussain Shah allied himself with Babur, he initially refused help to Humayun. Hindal tried to besiege Sehwan, an Arghun stronghold in northern Sindh. All the efforts proved futile.

In the meantime, Humayun married Hamida Banu, the daughter of a Shia Sufi spiritual master from Sindh named Shaikh Ali Akbar Jami, in September, 1541. Interestingly, the chief consort of Humayun, Bega Begum, was married to him roughly at the time when Hamida was born. There are hints of existence of unexpressed mutual feelings between Hamida and Hindal. But Hindal expressed it in a rather strange way after Hamida’s marriage to Humayun, by deserting him. Then the loyalties started deserting him increasingly.

Being refused by Maldeo Rao of Jodhpur (Marwar) for help, Humayun sought help of the Sodha Rajput, Rana Prasad of Amarkot (now Umerkot, Sindh). He, along with the pregnant Hamida Banu, reached Amarkot in August, 1542. Jalal (future Akbar) was born at Amarkot in October, 1542.

In 1543, finally the Arghuns of Sindh allied themselves with Humayun and he proceeded towards Kandahar with his ‘new army’ with a hope to unite with his brothers, then in Kabul, to reconquer ‘Hindustan’.

But he crossed the Indus, to reach near Kandahar in late 1543, to find that Askari was forced to acknowledge the authority of Kamran while the refusal by Hindal had earned him imprisonment. On the other hand, Sher Shah started building the strong and impregnable strategic fort of Rohtas near Jhelum in Pakistan’s Punjab (now a UNESCO World Heritage Site) to check the entry of the Timurids into India. To make matters worse, Askari was ordered by Kamran to capture Humayun who camped near Kandahar.

When Askari approached Humayun, he had nothing left in India to rely upon. He made quick yet calculated decision to flee further westward to the Shia Safavid Persia. He left behind the fourteen-month old Jalal (Akbar) at the mercy of the invaders. Askari not only adopted Jalal but also persuaded Kamran not to be harsh upon the baby. Kamran probably took Jalal as hostage. Nevertheless, the childhood of Jalal was to be spent in adventures in and around Kabul. Until Humayun’s return, Askari took care of Jalal and ensured his safety from Kamran.

Asylum in Persia

Humayun, Bega Begum, Hamida, and their forty loyal bodyguards took the northern route to Herat, then under the Safavid Persia, where they reached after a month-long torturous journey. At least here they received a royal welcome. But, it wasn’t unconditional.

At this time, Tahmasp I was the Safavid Sultan, the second one in his lineage, ruling since 1524. The imperial capital was Isfahan (Esfahan). The meeting between Humayun and Tahmasp in 1544 is depicted through a painting in the Chehel Sotun Palace of the city. Apparently, Hamida’s illustrious Shia background must have had strengthened the bonds between the two monarchs.

Secondly, Humayun was to cede the strategic fort and town of Kandahar to the Safavids as soon as he captured it.

Such conditional asylum was nothing unusual for any prudent ruler like Tahmasp who repeated the brilliant move in the case of the fugitive Ottoman prince, Bayezid, who happened to be very capable military leader and brilliant administrator, and could apparently succeed Suleiman the Magnificent, the greatest Ottoman emperor.

So Tahmasp supported Humayun with 12,000 troops to recover his lost domains, except Kandahar.

Regaining the Lost Ground

Humayun besieged and took Kandahar from Askari in mid-1545. To add to his happiness, a simultaneous siege at Kalinjar in India killed his arch-rival Sher Shah Suri in May. Nevertheless, Delhi would elude him for a decade.

Humayun proceeded to Kabul to confront Kamran, who found himself isolated as most of his allies and loyalists joined Humayun and forced him to leave Kabul without offering any resistance. This is how Humayun got Kabul in November, 1545.

Humayun showed his characteristic lethargy by not hunting down Kamran at this juncture. He instead indulged in festivities as he joined his lost son Jalal (Akbar) after a long. But the evasive Kamran managed to tease Humayun. Kamran took and lost Kabul twice, losing it forever in 1550. His resolution to dethrone Humayun was still there in his vindictive soul.

This was relatively easy time for him. In 1546, Humayun married Mah Chuchak Begum, a lady of military genius from Kabul. But this was to make the Kabul affairs complicated for his son Akbar as she bore Humayun two sons – Hakim and Farrukh.

In an attempt made by Kamran to retake Kabul in 1551, Hindal lost his life between Kabul and Peshawar. As a gesture of sympathy and gratitude, Jalal (Akbar) was married to Hindal’s daughter Ruqaiyyah Begum, who remained the chief consort of Akbar. Askari’s daughter Sakina too was married to Akbar.

Kamran did not give up. He asked for help from Sher Shah’s son, Islam Shah and the Ghakkars of western Punjab (now in Pakistan) who were loyal to Humayun, but was refused by both and instead captured and handed over to Humayun in 1552. A confused Humayun was under tremendous pressure this time from his loyals as the latter had lost too much and suffered from miseries for over a decade due to the former’s ill-sighted actions and indecisive behaviour. Humayun finally blinded Kamran and sent him on Hajj to Mecca, where he died in 1557.

Jalal (Akbar) was made the governor of Ghazni and he showed his mettle which he was going to prove in India over the rest of the 16th century.

Finally Delhi !

Sher Shah died in 1545. He was succeeded by Islam Shah Suri. In November 1554, Islam Shah Suri too died in Delhi, followed by quick successions to the throne. Islam’s minor son and successor, Firoz Shah’s was assassinated by his uncle, Muhammad Adil Shah. Adil Shah was overthrown by his brother-in-law, Ghazi Khan alias Ibrahim Shah. But Sikandar Shah declared his independence at Lahore and defeated Ibrahim at Farah near Mathura and became the emperor. This all happened within just six months, thus breaking the backbone of the Sur Empire.

Humayun had patiently waited for about 15 long years for the right moment to strike. And finally his penance paid off. With no rivals either in vicinity or between him and Delhi, he marched towards the de-facto capital of ‘Hindustan’ since centuries.

When the Sur civil war was going on, Humayun took Rohtas Fort, which Sher Shah had built to check Humayun’s entry into ‘Hindustan’, then Dipalpur and Lahore in early 1555. Finally, the decisive battle took place at Sirhind on 22nd June, 1555 in which, Sikandar Shah Suri was defeated and fled towards the Himalayas in today’s Himachal Pradesh. Still, Muhammad Adil Shah posed a considerable threat along with his trusted general, Hemchandra or Hemu. It was now Adil Shah’s and in effect, Hemu’s turn to wait for the better chance.

Humayun triumphantly entered Delhi in July, 1555. It was a hard won victory which made him realise that reliance upon astrology is good only for entertainment and not for practical and tactical judgements. But this time, ironically, he was proved wrong again, not by any foe but a mishap. He lost his life in late January, 1556 due to the injuries sustained while descending the stairs of Sher Mandal (probably Sher Shah’s library or perhaps an observatory) in Old Fort (Purana Qila) in Delhi.

More than three centuries later, after this Mughal Empire established by Humayun was really over in all respects, the British historian Lane Poole rightly said – “he tumbled out of life as he had tumbled through it.”

Persia vis-à-vis the Mughal Empire

Mughals were already highly Persianised. In fact, the term ‘Mughal’ itself is the Persian word for ‘Mongol’. Humayun’s exile opened the gates for further and faster Persianisation and if one is honest enough, he would call Mughal Empire a ‘Persianate’.

References :

- Humayun-nama by Gulbadan Begum

- The Life and Times of Humayun by Ishwari Prasad

- Humayun Badshah by S.K.Banerji

- Advanced Study in the History of Medieval India by J.L.Mehta

- The Mughal world : Life in India’s Last Golden Age by Eraly Abraham

- Akbar, the Greatest Mogul by S.M.Burkhe

- Medieval India under Mohammedan Rule by Stanley Lane-Poole

- Domesticity and Power in the Early Mughal World by Ruby Lal