In the first part of this article we saw that the otherwise common structure of land divisions has remained more-or-less the same for over 2,000 years. There were small changes as generations passed, new divisions came into being, and the names changed, but the structure essentially remained the same.

But what of the lowest unit of these sub-divisions—the village?

By far, all through the various changes, handovers, divisions and transfers of lands between rulers and dynasties, the village remained an independent and a self-sufficient unit. Undoubtedly, villages and villagers suffered the most during wartime, or campaigns by various kings and warlords, yet in administrative terms, the village wasn’t affected (significantly) by the mergers, takeovers, and acquisitions by empires.

During the reign of Chh. Shivaji, one notable change that the administrative system underwent was the visible hand of the central government. The indirect system of tax collection was abolished, and government officers were appointed in villages to manage matters of tax. This greatly improved tax collections because it assigned responsibility to government officers, rather than local lords.

Yet, the republican nature of the village remained intact.

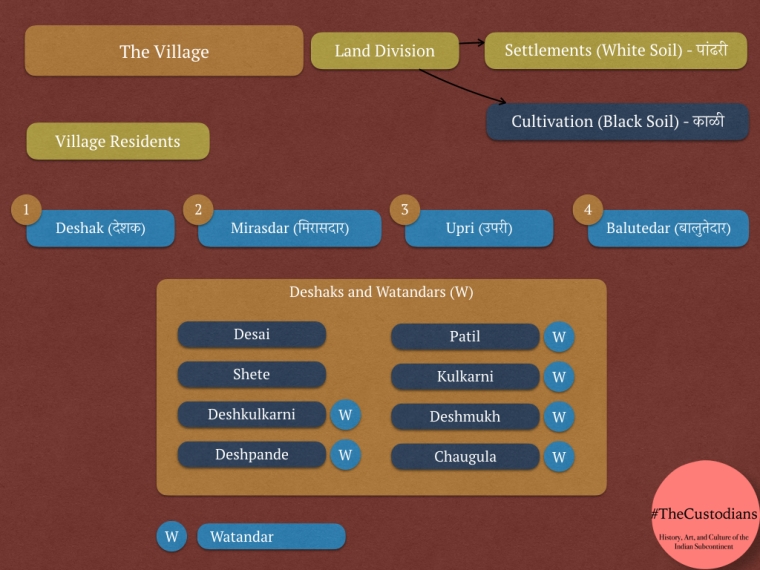

The Village: Land Division

Villages during this period were typically divided in two parts, based on the land quality: one for the settlements and the other for cultivation. The section for the settlements, made of the white soil was called gharthan, and the one with black soil was allocated for cultivation. The word pandhari, meaning white, later took on the meaning to refer the settlers on the white soil.

The Village: Residents

There four types or groups of residents in a village. These were:

- Deshak (देशक) or Watandars (वतनदार): Deshaks were officers of the village, and revenue-paying heredity owners of land. Watandars did not pay revenue for the land, instead the served the kingdom.

- Thalkari (थलकरी) or Mirasdars:(मिरासदार) Thalkari or Mirasdar paid land revenue, but were not officials and formed a large part of the village community, and were hereditary owners of the land. Mirasdar is an Arabic word (Miras=Inherit)for Thalkari.

- Upris (उपरी): The Upris were tenant-at-will, of government land, held land on a renewable basis, called Kaulnama (कौलनामा), also paid land revenue, but were tenants, rather than owners. They did not enjoy the advantage and the position of the Mirasdars.

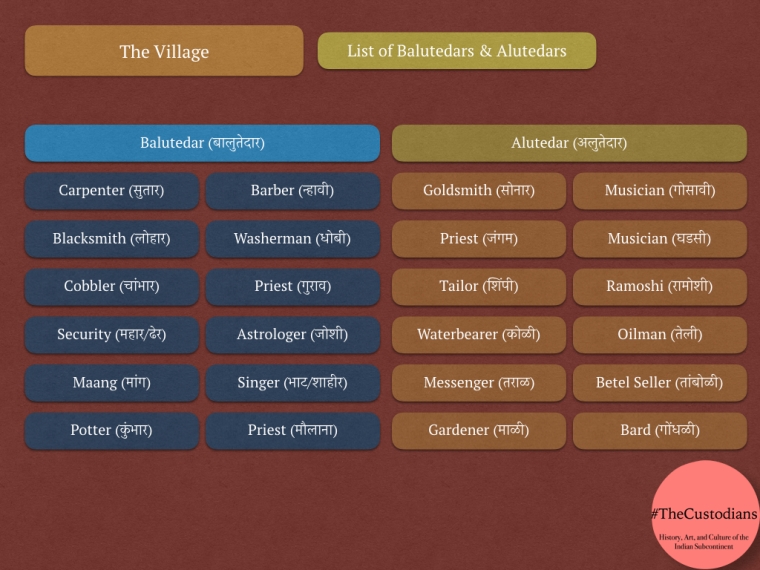

- Balutedar (बालुतेदार) & Alutedars (अलुतेदार): In simplest terms these were the “service-providers” to the village. Baluta signifies a share of grain (or agricultural produce) and in most cases, these folks were paid in kind, annually.

The Deshmukh, was the head of all the Patils of the villages in a Paragana, while the Deshpande was the head of all the Kulkarnis. Of the various Deshaks the Patil, undoubtedly was the most important person, in the village. He was the village headman, and was responsible for peace and order, revenue management, and paying revenues to the government. It was not necessary that he lived an affluent life, but wielded much power.

In a saying in old Marathi, a bride prefers a Patilas her groom, even if there is no grain in the house.

उतरंडीला नसेना दाणा, पण दादला असावा पाटील राणा.

Typically, there were twelve Balutedars (बारा बालुतेदार) and an equal number of Alutedars. We say typically, because this number varied from village to village, possibly due to the size of the village. The Balutedars served the village, where as the Alutedars (also known as Khooms) served in the Peth or the market of the village.

The village also practiced its own judicial system, known as the Gotsabha (गोतसभा). All residents of the village had representation in the Gotsabha, except the tenants — the Upris. The Mahar, was a Watandar of the village, and performed a significant task in the village community with respect to providing security. Grant Duff, praises the Mahar community as hard-working and intelligent. In one instance we have the Mahar being called up to resolve boundary disputes and fix the boundaries of villages under Torna fort.

Various documents give an insight into the independent functioning of the village in Deccan. While villages faced a severe brunt during war and plunder, and their top-bosses changed with the fates of the kings, the village remained an independent, self-governing, republican unit.

References

- Habib, Irfan. The Agrarian System of Mughal India: 1556-1707. New Delhi: Oxford U, 2004. Print.

- Kulakarṇi, A. R. Maharashtra in the Age of Shivaji. Poona: Deshmukh, 2008. Print.

- Sen, Surendra Nath. “Village Communities.” Administrative System of the Marathas. 2nd ed. Calcutta: K.P. Bagchi, 1976. 143. Print.

- Gune, Vithal Trimbak. The Judicial System of the Marathas. Poona: Deccan College PGRI, 1953.

- Kulkarni, A. R. शिवकालीन महाराष्ट्र (Shivkaleen Maharashtra). Pune: Rajhans, 1996

Post Script:

I am looking for helps with translations of the following terms: Security (महार/ढेर), Singer (भाट/शाहीर), Priest (मौलाना), Musician (गोसावी), Musician (घडसी), Ramoshi (रामोशी), as it applies in the above context.